The Secretive Company That Might End Privacy as We Know It

A little-known start-up helps law enforcement match photos of unknown people to their online images — and “might lead to a dystopian future or something,” a backer says.

Credit...Adam Ferriss

By Kashmir Hill

Jan. 18, 2020

Until recently, Hoan Ton-That’s greatest hits included an obscure iPhone game and an app that let people put Donald Trump’s distinctive yellow hair on their own photos.

Then Mr. Ton-That — an Australian techie and onetime model — did something momentous: He invented a tool that could end your ability to walk down the street anonymously, and provided it to hundreds of law enforcement agencies, ranging from local cops in Florida to the F.B.I. and the Department of Homeland Security.

His tiny company, Clearview AI, devised a groundbreaking facial recognition app. You take a picture of a person, upload it and get to see public photos of that person, along with links to where those photos appeared. The system — whose backbone is a database of more than three billion images that Clearview claims to have scraped from Facebook, YouTube, Venmo and millions of other websites — goes far beyond anything ever constructed by the United States government or Silicon Valley giants.

Federal and state law enforcement officers said that while they had only limited knowledge of how Clearview works and who is behind it, they had used its app to help solve shoplifting, identity theft, credit card fraud, murder and child sexual exploitation cases.

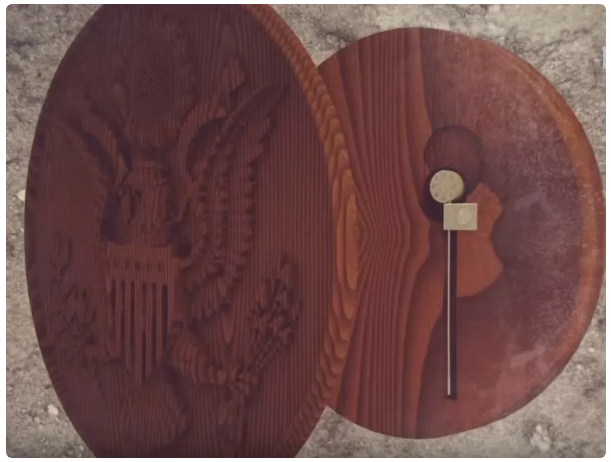

Until now, technology that readily identifies everyone based on his or her face has been taboo because of its radical erosion of privacy. Tech companies capable of releasing such a tool have refrained from doing so; in 2011, Google’s chairman at the time said it was the one technology the company had held back because it could be used “in a very bad way.” Some large cities, including San Francisco, have barred police from using facial recognition technology.

But without public scrutiny, more than 600 law enforcement agencies have started using Clearview in the past year, according to the company, which declined to provide a list. The computer code underlying its app, analyzed by The New York Times, includes programming language to pair it with augmented-reality glasses; users would potentially be able to identify every person they saw. The tool could identify activists at a protest or an attractive stranger on the subway, revealing not just their names but where they lived, what they did and whom they knew.

And it’s not just law enforcement: Clearview has also licensed the app to at least a handful of companies for security purposes.

“The weaponization possibilities of this are endless,” said Eric Goldman, co-director of the High Tech Law Institute at Santa Clara University. “Imagine a rogue law enforcement officer who wants to stalk potential romantic partners, or a foreign government using this to dig up secrets about people to blackmail them or throw them in jail.”

Clearview has shrouded itself in secrecy, avoiding debate about its boundary-pushing technology. When I began looking into the company in November, its website was a bare page showing a nonexistent Manhattan address as its place of business. The company’s one employee listed on LinkedIn, a sales manager named “John Good,” turned out to be Mr. Ton-That, using a fake name. For a month, people affiliated with the company would not return my emails or phone calls.

While the company was dodging me, it was also monitoring me. At my request, a number of police officers had run my photo through the Clearview app. They soon received phone calls from company representatives asking if they were talking to the media — a sign that Clearview has the ability and, in this case, the appetite to monitor whom law enforcement is searching for.

Facial recognition technology has always been controversial. It makes people nervous about Big Brother. It has a tendency to deliver false matches for certain groups, like people of color. And some facial recognition products used by the police — including Clearview’s — haven’t been vetted by independent experts.

Clearview’s app carries extra risks because law enforcement agencies are uploading sensitive photos to the servers of a company whose ability to protect its data is untested.

The company eventually started answering my questions, saying that its earlier silence was typical of an early-stage start-up in stealth mode. Mr. Ton-That acknowledged designing a prototype for use with augmented-reality glasses but said the company had no plans to release it. And he said my photo had rung alarm bells because the app “flags possible anomalous search behavior” in order to prevent users from conducting what it deemed “inappropriate searches.”

In addition to Mr. Ton-That, Clearview was founded by Richard Schwartz — who was an aide to Rudolph W. Giuliani when he was mayor of New York — and backed financially by Peter Thiel, a venture capitalist behind Facebook and Palantir.

Another early investor is a small firm called Kirenaga Partners. Its founder, David Scalzo, dismissed concerns about Clearview making the internet searchable by face, saying it’s a valuable crime-solving tool.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that because information constantly increases, there’s never going to be privacy,” Mr. Scalzo said. “Laws have to determine what’s legal, but you can’t ban technology. Sure, that might lead to a dystopian future or something, but you can’t ban it.”

Mr. Ton-That, 31, grew up a long way from Silicon Valley. In his native Australia, he was raised on tales of his royal ancestors in Vietnam. In 2007, he dropped out of college and moved to San Francisco. The iPhone had just arrived, and his goal was to get in early on what he expected would be a vibrant market for social media apps. But his early ventures never gained real traction.

In 2009, Mr. Ton-That created a site that let people share links to videos with all the contacts in their instant messengers. Mr. Ton-That shut it down after it was branded a “phishing scam.” In 2015, he spun up Trump Hair, which added Mr. Trump’s distinctive coif to people in a photo, and a photo-sharing program. Both fizzled.

Dispirited, Mr. Ton-That moved to New York in 2016. Tall and slender, with long black hair, he considered a modeling career, he said, but after one shoot he returned to trying to figure out the next big thing in tech. He started reading academic papers on artificial intelligence, image recognition and machine learning.

Mr. Schwartz and Mr. Ton-That met in 2016 at a book event at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. Mr. Schwartz, now 61, had amassed an impressive Rolodex working for Mr. Giuliani in the 1990s and serving as the editorial page editor of The New York Daily News in the early 2000s. The two soon decided to go into the facial recognition business together: Mr. Ton-That would build the app, and Mr. Schwartz would use his contacts to drum up commercial interest.

Police departments have had access to facial recognition tools for almost 20 years, but they have historically been limited to searching government-provided images, such as mug shots and driver’s license photos. In recent years, facial recognition algorithms have improved in accuracy, and companies like Amazon offer products that can create a facial recognition program for any database of images.

Mr. Ton-That wanted to go way beyond that. He began in 2016 by recruiting a couple of engineers. One helped design a program that can automatically collect images of people’s faces from across the internet, such as employment sites, news sites, educational sites, and social networks including Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and even Venmo. Representatives of those companies said their policies prohibit such scraping, and Twitter said it explicitly banned use of its data for facial recognition.

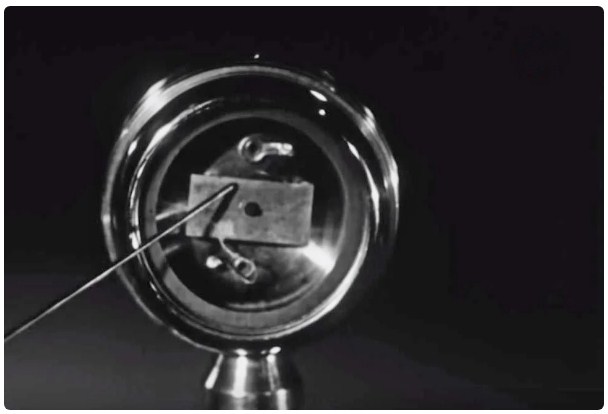

Another engineer was hired to perfect a facial recognition algorithm that was derived from academic papers. The result: a system that uses what Mr. Ton-That described as a “state-of-the-art neural net” to convert all the images into mathematical formulas, or vectors, based on facial geometry — like how far apart a person’s eyes are. Clearview created a vast directory that clustered all the photos with similar vectors into “neighborhoods.” When a user uploads a photo of a face into Clearview’s system, it converts the face into a vector and then shows all the scraped photos stored in that vector’s neighborhood — along with the links to the sites from which those images came.

Mr. Schwartz paid for server costs and basic expenses, but the operation was bare bones; everyone worked from home. “I was living on credit card debt,” Mr. Ton-That said. “Plus, I was a Bitcoin believer, so I had some of those.”

By the end of 2017, the company had a formidable facial recognition tool, which it called Smartcheckr. But Mr. Schwartz and Mr. Ton-That weren’t sure whom they were going to sell it to.

Maybe it could be used to vet babysitters or as an add-on feature for surveillance cameras. What about a tool for security guards in the lobbies of buildings or to help hotels greet guests by name? “We thought of every idea,” Mr. Ton-That said.

One of the odder pitches, in late 2017, was to Paul Nehlen — an anti-Semite and self-described “pro-white” Republican running for Congress in Wisconsin — to use “unconventional databases” for “extreme opposition research,” according to a document provided to Mr. Nehlen and later posted online. Mr. Ton-That said the company never actually offered such services.

The company soon changed its name to Clearview AI and began marketing to law enforcement. That was when the company got its first round of funding from outside investors: Mr. Thiel and Kirenaga Partners. Among other things, Mr. Thiel was famous for secretly financing Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit that bankrupted the popular website Gawker. Both Mr. Thiel and Mr. Ton-That had been the subject of negative articles by Gawker.

“In 2017, Peter gave a talented young founder $200,000, which two years later converted to equity in Clearview AI,” said Jeremiah Hall, Mr. Thiel’s spokesman. “That was Peter’s only contribution; he is not involved in the company.”

Even after a second funding round in 2019, Clearview remains tiny, having raised $7 million from investors, according to Pitchbook, a website that tracks investments in start-ups. The company declined to confirm the amount.

In February, the Indiana State Police started experimenting with Clearview. They solved a case within 20 minutes of using the app. Two men had gotten into a fight in a park, and it ended when one shot the other in the stomach. A bystander recorded the crime on a phone, so the police had a still of the gunman’s face to run through Clearview’s app.

They immediately got a match: The man appeared in a video that someone had posted on social media, and his name was included in a caption on the video. “He did not have a driver’s license and hadn’t been arrested as an adult, so he wasn’t in government databases,” said Chuck Cohen, an Indiana State Police captain at the time.

The man was arrested and charged; Mr. Cohen said he probably wouldn’t have been identified without the ability to search social media for his face. The Indiana State Police became Clearview’s first paying customer, according to the company. (The police declined to comment beyond saying that they tested Clearview’s app.)

Clearview deployed current and former Republican officials to approach police forces, offering free trials and annual licenses for as little as $2,000. Mr. Schwartz tapped his political connections to help make government officials aware of the tool, according to Mr. Ton-That. (“I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to help Hoan build Clearview into a mission-driven organization that’s helping law enforcement protect children and enhance the safety of communities across the country,” Mr. Schwartz said through a spokeswoman.)

The company’s main contact for customers was Jessica Medeiros Garrison, who managed Luther Strange’s Republican campaign for Alabama attorney general. Brandon Fricke, an N.F.L. agent engaged to the Fox Nation host Tomi Lahren, said in a financial disclosure report during a congressional campaign in California that he was a “growth consultant” for the company. (Clearview said that it was a brief, unpaid role, and that the company had enlisted Democrats to help market its product as well.)

The company’s most effective sales technique was offering 30-day free trials to officers, who then encouraged their acquisition departments to sign up and praised the tool to officers from other police departments at conferences and online, according to the company and documents provided by police departments in response to public-record requests. Mr. Ton-That finally had his viral hit.

In July, a detective in Clifton, N.J., urged his captain in an email to buy the software because it was “able to identify a suspect in a matter of seconds.” During the department’s free trial, Clearview had identified shoplifters, an Apple Store thief and a good Samaritan who had punched out a man threatening people with a knife.

Photos “could be covertly taken with telephoto lens and input into the software, without ‘burning’ the surveillance operation,” the detective wrote in the email, provided to The Times by two researchers, Beryl Lipton of MuckRock and Freddy Martinez of Open the Government. They discovered Clearview late last year while looking into how local police departments are using facial recognition.

According to a Clearview sales presentation reviewed by The Times, the app helped identify a range of individuals: a person who was accused of sexually abusing a child whose face appeared in the mirror of someone’s else gym photo; the person behind a string of mailbox thefts in Atlanta; a John Doe found dead on an Alabama sidewalk; and suspects in multiple identity-fraud cases at banks.

In Gainesville, Fla., Detective Sgt. Nick Ferrara heard about Clearview last summer when it advertised on CrimeDex, a list-serv for investigators who specialize in financial crimes. He said he had previously relied solely on a state-provided facial recognition tool, FACES, which draws from more than 30 million Florida mug shots and Department of Motor Vehicle photos.

Sergeant Ferrara found Clearview’s app superior, he said. Its nationwide database of images is much larger, and unlike FACES, Clearview’s algorithm doesn’t require photos of people looking straight at the camera.

“With Clearview, you can use photos that aren’t perfect,” Sergeant Ferrara said. “A person can be wearing a hat or glasses, or it can be a profile shot or partial view of their face.”

He uploaded his own photo to the system, and it brought up his Venmo page. He ran photos from old, dead-end cases and identified more than 30 suspects. In September, the Gainesville Police Department paid $10,000 for an annual Clearview license.

Federal law enforcement, including the F.B.I. and the Department of Homeland Security, are trying it, as are Canadian law enforcement authorities, according to the company and government officials.

Despite its growing popularity, Clearview avoided public mention until the end of 2019, when Florida prosecutors charged a woman with grand theft after two grills and a vacuum were stolen from an Ace Hardware store in Clermont. She was identified when the police ran a still from a surveillance video through Clearview, which led them to her Facebook page. A tattoo visible in the surveillance video and Facebook photos confirmed her identity, according to an affidavit in the case.

‘We’re All Screwed’

Mr. Ton-That said the tool does not always work. Most of the photos in Clearview’s database are taken at eye level. Much of the material that the police upload is from surveillance cameras mounted on ceilings or high on walls.

“They put surveillance cameras too high,” Mr. Ton-That lamented. “The angle is wrong for good face recognition.”

Despite that, the company said, its tool finds matches up to 75 percent of the time. But it is unclear how often the tool delivers false matches, because it has not been tested by an independent party such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology, a federal agency that rates the performance of facial recognition algorithms.

“We have no data to suggest this tool is accurate,” said Clare Garvie, a researcher at Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology, who has studied the government’s use of facial recognition. “The larger the database, the larger the risk of misidentification because of the doppelgänger effect. They’re talking about a massive database of random people they’ve found on the internet.”

But current and former law enforcement officials say the app is effective. “For us, the testing was whether it worked or not,” said Mr. Cohen, the former Indiana State Police captain.

One reason that Clearview is catching on is that its service is unique. That’s because Facebook and other social media sites prohibit people from scraping users’ images — Clearview is violating the sites’ terms of service.

“A lot of people are doing it,” Mr. Ton-That shrugged. “Facebook knows.”

Jay Nancarrow, a Facebook spokesman, said the company was reviewing the situation with Clearview and “will take appropriate action if we find they are violating our rules.”

Mr. Thiel, the Clearview investor, sits on Facebook’s board. Mr. Nancarrow declined to comment on Mr. Thiel's personal investments.

Some law enforcement officials said they didn’t realize the photos they uploaded were being sent to and stored on Clearview’s servers. Clearview tries to pre-empt concerns with an F.A.Q. document given to would-be clients that says its customer-support employees won’t look at the photos that the police upload.

In an August memo that Clearview provided to potential customers, including the Atlanta Police Department and the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office in Florida, Mr. Clement said law enforcement agencies “do not violate the federal Constitution or relevant existing state biometric and privacy laws when using Clearview for its intended purpose.”

Mr. Clement, now a partner at Kirkland & Ellis, wrote that the authorities don’t have to tell defendants that they were identified via Clearview, as long as it isn’t the sole basis for getting a warrant to arrest them. Mr. Clement did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The memo appeared to be effective; the Atlanta police and Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office soon started using Clearview.

Because the police upload photos of people they’re trying to identify, Clearview possesses a growing database of individuals who have attracted attention from law enforcement. The company also has the ability to manipulate the results that the police see. After the company realized I was asking officers to run my photo through the app, my face was flagged by Clearview’s systems and for a while showed no matches. When asked about this, Mr. Ton-That laughed and called it a “software bug.”

“It’s creepy what they’re doing, but there will be many more of these companies. There is no monopoly on math,” said Al Gidari, a privacy professor at Stanford Law School. “Absent a very strong federal privacy law, we’re all screwed.”

Mr. Ton-That said his company used only publicly available images. If you change a privacy setting in Facebook so that search engines can’t link to your profile, your Facebook photos won’t be included in the database, he said.

But if your profile has already been scraped, it is too late. The company keeps all the images it has scraped even if they are later deleted or taken down, though Mr. Ton-That said the company was working on a tool that would let people request that images be removed if they had been taken down from the website of origin.

Woodrow Hartzog, a professor of law and computer science at Northeastern University in Boston, sees Clearview as the latest proof that facial recognition should be banned in the United States.

“We’ve relied on industry efforts to self-police and not embrace such a risky technology, but now those dams are breaking because there is so much money on the table,” Mr. Hartzog said. “I don’t see a future where we harness the benefits of face recognition technology without the crippling abuse of the surveillance that comes with it. The only way to stop it is to ban it.”

Where Everybody Knows Your Name

During a recent interview at Clearview’s offices in a WeWork location in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, Mr. Ton-That demonstrated the app on himself. He took a selfie and uploaded it. The app pulled up 23 photos of him. In one, he is shirtless and lighting a cigarette while covered in what looks like blood.

Mr. Ton-That then took my photo with the app. The “software bug” had been fixed, and now my photo returned numerous results, dating back a decade, including photos of myself that I had never seen before. When I used my hand to cover my nose and the bottom of my face, the app still returned seven correct matches for me.

Police officers and Clearview’s investors predict that its app will eventually be available to the public.

Mr. Ton-That said he was reluctant. “There’s always going to be a community of bad people who will misuse it,” he said.

Even if Clearview doesn’t make its app publicly available, a copycat company might, now that the taboo is broken. Searching someone by face could become as easy as Googling a name. Strangers would be able to listen in on sensitive conversations, take photos of the participants and know personal secrets. Someone walking down the street would be immediately identifiable — and his or her home address would be only a few clicks away. It would herald the end of public anonymity.

Asked about the implications of bringing such a power into the world, Mr. Ton-That seemed taken aback.

“I have to think about that,” he said. “Our belief is that this is the best use of the technology.”

Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Gabriel J.X. Dance and Aaron Krolik contributed reporting. Kitty Bennett contributed research.